“In a world organized in accordance with Keynes’ specifications, there would be a constant race between the printing press and the business agents of the trade unions, with the problem of unemployment largely solved if the printing press could maintain a constant lead.”

Jacob Viner (1892 -1970) in “Mr. Keynes on the Causes of Unemployment

Summary

Looking back at the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) from 1775 to today, one realises that the obsession with inflation is quite a recent phenomenon. Inflation and what causes it, are not easy things to understand. As economist Herbert Stein, then a top adviser to US President Richard Nixon, called inflation “a hydra-headed monster” that “came in various forms—sometimes led by wages, sometimes by prices, by foods, by oil; sometimes it was domestic and sometimes imported.” However, in my view, there is one indicator that is the most useful in understanding inflation and that is: Wages. Despite the excessive money printing since the 2008, what we haven’t seen is an increase in wages. Inflation is not yet a serious headwind but it could be soon enough, as labour markets improve further. By labour market improvement, I do not mean just low unemployment rates. Instead of focusing on the unemployment rate, we should watch the rate at which workers are switching between jobs, as a precursor of increased inflation. When job-switching picks up, wages will pick up and so will inflation. My gut tells me that we will see a short burst of high inflation but over the medium-term, inflation is not a big risk.

The COVID-19 pandemic is fading fast and the vaccine is working better than many would have imagined. The UK and the US have done a great job and the European Union (EU) will inevitably follow suit as they get their vaccination program in order. In the sea of good news on the COVID-19 front, the news from India is not so positive, where infections continue to mount as do fatalities. One reason is the low level of vaccination. In India, less than 2% of the country’s population have been fully vaccinated and less than 8% have received the first dose. By comparison, over 42.7% of the population in the US and over 60% of the population in the UK have received at least one dose of the vaccine. Vaccination is the only way out of this crisis. New variants are bound to rise as the virus mutates. Drug companies are already working on booster jabs to tackle this eventuality. In the US, the administration of US President Joe Biden continues to announce more spending and the governments of Germany and Italy have also signalled they are willing to run large deficits this year, in order to support their economies. As the re-opening continues, equity markets have continued to rally. The S&P 500 Index’s (SPX) return for the year is already in double digits.

Inflation will return, the question is when

As the re-opening of the US economy continues, there’s once again the talk of inflation and as bond yields rise, the talk keeps getting louder. In this world of fiat currency and money printing that we find ourselves in, inflation will inevitably return, the only question is when.

The case for inflation is not straightforward, particularly if you look at the history of inflation in the US. Looking back at the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) from 1775 to today, you realise that the obsession with inflation is just a recent phenomenon.

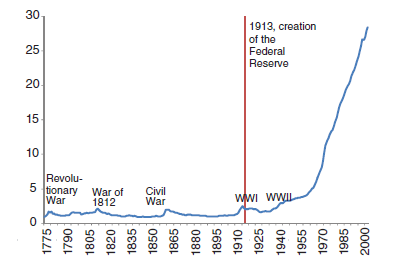

The chart below by US Economists Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, plots the US consumer price level from 1775 (set equal to one) until 2012.You will notice that the price level was stable to disinflationary for almost a century and a half from 1775. Inflation then built up in the 1930s and 40s and exploded in the 1970s and 80s. For the last three decades, inflation has been quite stable and falling. Recall, the US Federal Reserve (Fed), the guardian of US monetary policy, was created by an act of Congress in 1913.

- In 1913, prices were only around +20% higher than in 1775, the year of the American Revolutionary War and -40% lower than a century prior during the War of 1812 (June 1812 – February 1815)

- By comparison, in 2013, consumer prices were about 24 times higher than they were in 1913. An astounding increase in the price level since the creation of the Federal Reserve. This pattern, in varying orders of magnitude, repeats itself across nearly every country

Consumer price index (CPI), United States, 1775-2012 ( level 1775 =1)

Source: Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) and Reinhart and Rogoff (2009)

When the Federal Reserve was first established in 1913, the US Congress directed it only to “furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper” and “to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States.” In effect, the Fed’s founding purpose was to promote “financial stability” to stem banking panics. There is no mention of a “price stability” mandate in the original version of the legislation. Indeed, the word inflation does not appear at all in the document. The original Act assumed continued adherence to the gold standard regime, which tended to keep inflation under control automatically over the long run. High inflation was still largely seen by the founders of the Fed, as a relatively rare phenomenon associated with wars and their immediate aftermath.

Inflation didn’t take off until two decades after the creation of the Fed when the United States under President Franklin D. Roosevelt went off the gold standard in 1933 and then inflation exploded when the US abandoned the remnants of the “gold standard” system completely in 1973, under President Richard Nixon.

The need to control inflation in the aftermath of 1973 led to the 1977 Federal Reserve Reform Act signed into law by President Jimmy Carter. It amended the original Act by explicitly directing the Federal Reserve to “promote the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” However, it wasn’t until 2012 that the Fed adopted a numerical definition of the mandated “stable prices” goal of 1977. The numerical definition stated that the Fed sought +2% inflation, as measured by the Commerce Department’s Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index over the medium run. US Core PCE is currently at +1.4% (see chart below). It has been below the Fed’s target of +2% for 46 of the 49 quarters since Q4 2008, rising only briefly above +2% on a few occasions

So the last 250 years of US inflation can be summarised as – a very long period of little or no inflation, a couple of decades of high inflation in the 1970s-80 and back to more than three decades of low inflation.

U.S. Core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price YoY change (1960 – present)

Source: Bloomberg

The adoption of fiat money and money printing changed everything and thus the obsession with inflation. Money printing has become a global phenomenon even in emerging markets, particularly in Asia, getting on the bandwagon during the last decade. In the March 2020 Market Viewpoints, I wrote on how we got to a world of money-printing referring to the era of President Nixon, which saw the US abandon the gold standard completely.

The period since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-2008 is particularly significant, as inflation did not taken off despite record money printing, excessive debt, technological innovations, labour market changes and a downward pressure on wages – all having exerted downward pressure on inflation.

So what’s the prognosis for inflation ahead?

Inflation and what causes it, is not an easy thing to understand. As economist Herbert Stein, then a top adviser to President Nixon, called inflation “a hydra-headed monster” that “came in various forms—sometimes led by wages, sometimes by prices, by foods, by oil; sometimes it was domestic and sometimes imported.”

However, in my view, there is one indicator that is the most useful in understanding inflation and that is: Wages. Despite the excessive money printing since the GFC, what we haven’t seen is an increase in wages. Inflation no doubt is a monetary phenomenon (and we have seen plenty of money printing) but the money has to find its way through to prices. Apart from one time shocks such as high commodity prices, the sustainable way to higher prices is through an increase in wages – and we haven’t seen that over the last decade or so.

The key reason that wages haven’t increased is due to the change in market structures. Service-based economies have overtaken the largely manufacturing-driven economies. The latter historically has had more “unionised labour” and therefore an influence on wages. The former less so. As big corporations have gotten even bigger, they have started resembling “monopolies” which has made the “employer’s” position stronger vis-à-vis wages. Also, the increased use of automation and machines have made labour more dispensable.

Inflation is not yet a serious headwind but it could be soon enough, as labour markets improve further. By labour market improvement, I do not mean just low unemployment rates. Instead of focusing on just the unemployment rate, we should watch the rate at which workers are switching between jobs, as a precursor of increased inflation. When job-switching picks up, wages will pick up and so will inflation.

As Nobel Prize-winning labour economist Chris Pissarides puts it – “The biggest reason for wage rises is competition, either actual turnover or the threat of turnover. If we’re observing declining labour turnover, that should have an impact on productivity and wage increases.”

Workers can demand higher wages only if they have outside offers, regardless of the unemployment rate. Job switchers in turn also improve the bargaining position of workers who stay in their jobs, by encouraging employers to pay more to retain them. According to Giuseppe Moscarini, a labour economist at Yale University, for the average U.S. worker, 40% of wage growth over their working lifetime comes from job switching, rather than through experience or an increase in skills.

Data indicate that in the US, job-switching which used to be as high 7% per quarter in 2000, fell by more than half to as low as 3% per quarter in 2009 and only rose to 5.8% a decade later. So it’s not just the “velocity of money” but the “velocity of job-switching” that needs to change for wages to increase and feed into prices.

In this respect, the policies of the administration of President Joe Biden on tax, tackling income inequality and raising the minimum wage are going to be significant over the coming months. As a preview of it, this Tuesday, Biden signed an executive order requiring that Federal contractors pay a $15-an-hour minimum wage. The current minimum wage for workers performing work on covered Federal contracts is $10.95. The Federal minimum wage was last increased over a decade ago, in July 2009.

My gut tells me that we will see a short burst of high inflation but over the medium-term, inflation is not be a big risk.

Markets and the Economy

The COVID pandemic is fading fast and the vaccine is working better than many would have imagined. In the UK, which is a shining example to the world for its early and successful vaccination program, 40 million people now live in “COVID-free” areas, where two or fewer cases were recorded in the last week and data is indicating that the vaccine reduces hospitalisation by -98%. Deaths from the COVID-19 virus in the UK are now falling by more than -20% per week and overall mortality from all causes now is below the long-term average.

According to Sarah Walker, Professor of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology at Oxford and Chief Investigator on the Office of National Statistics’ (ONS) COVID-19 Infection Survey – “we’ve moved from a pandemic to an endemic situation.”

Across the pond in the US, 29.1% of the population has now been fully vaccinated, and 42.7% of people have received at least one dose. New York State plans to open mass-vaccination sites for walk-ins beginning this week. On Tuesday, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said people who are fully vaccinated don’t need to wear face masks when walking, hiking, biking, running alone or gathering in small groups outside. They follow mounting scientific evidence which indicates that the risk of infection is low outdoors, especially among people who are vaccinated.

In the sea of good news on the COVID-19 front, the news from India is not so positive, where a new variant has been detected. Infections continue to mount as do fatalities. In India, less than 2% of the country’s people have been fully vaccinated and less than 8% have received the first dose. Of particular concern is the rising number of cases and deaths among the younger population. Experts have long held the view that the younger population is more immune to the virus and its fatal effects. What if a new variant affects the young as much as the old? Vaccination is the only way out of this crisis. New variants are bound to rise as the virus mutates. Drug companies are already working on booster jabs to tackle this eventuality.

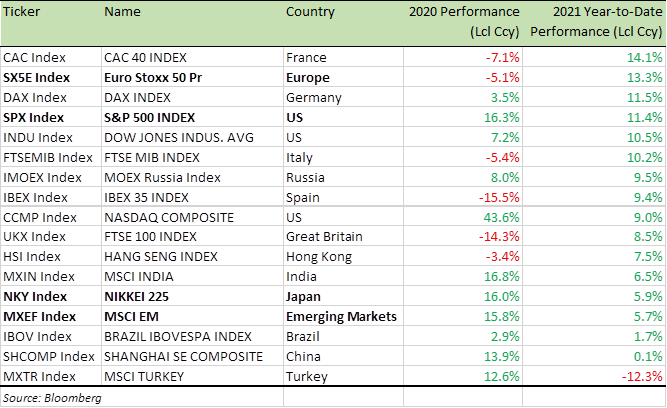

Benchmark Equity Index Performance (2020 and 2021 YTD)

Overall, the message on dealing with COVID-19 and therefore the boost to the economy is an upbeat one as per the latest forecasts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Equity markets have continued to rally. The S&P 500 Index’s (SPX) return for the year is already in double digits as the table above indicates.

- The IMF expects the global economy to grow +6% this year, the most since 1980. That is an upgrade from a projection for +5.5% growth the IMF made in January. The pandemic cut global output by an estimated 3.3% in 2020, the worst peacetime outcome since the Great Depression

- The US and China are the biggest drivers of this recovery. The US economy is projected to expand +6.4% this year. The IMF earlier projected +5.1% growth in 2021. China’s economy is projected to expand +8.4% this year, up from an earlier forecast of +8.1%

As more people in the US receive vaccinations, stimulus payments reached households and businesses re-opened, the US consumer confidence index has increased to 121.7 in April from a revised 109.0 in March, marking the fourth straight month of gains. US consumers also seem more upbeat regarding their income prospects due to an improving job market and the re-opening of the economy. This continued rise in confidence bodes well for consumer spending for the rest of the year.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) this week held interest rates near zero even as the recovery has picked up.Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has repeatedly stressed that he wants to see progress show up in economic data, rather than in forecasts before the Fed raises rates or scales back the bond purchases. Last week, San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said – “We’re just in the beginning stages of seeing these good data. We’re going to need repeated months of this before we can distinguish optimism about the future from the realization of the future.”

On the fiscal front, US President Biden is set to announce a $1.8 trillion plan aimed at low and middle-income families and it will include help towards childcare, education, paid leave etc. It will include $1 trillion in new spending over 10 years and $800 billion in tax cuts, albeit not new tax cuts but extensions of some tax breaks already in place. To pay for the new programs, the administration proposes raising the income tax and capital gains tax on wealthy households making more than $1 million a year.

In the Eurozone, the European Central Bank (ECB) said last week that it would keep its key interest rate at -0.5% and continue to buy Eurozone debt under an emergency €1.85 trillion bond-buying program which will last at least until March 2022. The ECB also said it would buy those bonds at a “significantly higher pace” during the first months of this year, repeating a pledge made last month. Governments in Germany and Italy have also signalled they are willing to run large deficits this year to support their economies.

On Monday, Italy’s newly minted Prime Minister Mario Draghi unveiled a €220 bn European Union (EU)-funded recovery package for a radical restructuring of Italy’s economy as it seeks to bounce back from its deepest recession since the second world War. Hit by lockdown measures, Italy’s chronically sluggish economy shrank by -9% last year and is still mired in recession. “The destiny of the country lies in this set of projects,” Draghi told the lower house of Parliament as he presented his plan. The success of this plan is critical not only for Italy, but also to the credibility of the EU’s post-COVID-19 recovery effort. Separately, Germany’s public sector deficit reached €189.2 billion in 2020, the first deficit since 2013 and the highest budget shortfall since German reunification three decades ago, the German Statistics Office said. The spending spree is set to continue, with German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz promising to do whatever was needed to enable Germany to spend its way out of a coronavirus-induced economic slump.

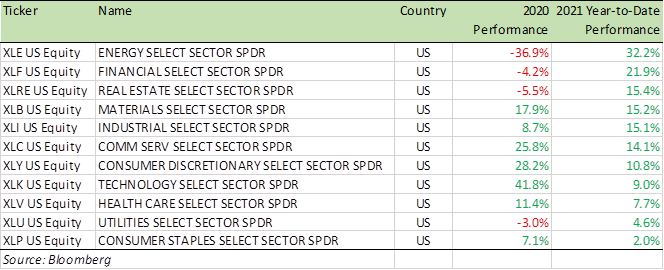

Benchmark US equity sector performance (2020 and 2021 YTD)

In summary, therefore, monetary and fiscal accommodation continues across the globe as growth accelerates in the US, China and the UK.

Inflation will be a factor as outlined in the first section above but it still seems a few months away. I continue to be bullish on equities and expect European equities, which have lagged their US counterparts for much of last year, to continue to catch up as global growth accelerates. Growth stocks will see-saw but sell-offs are an opportunity to “buy the dip” in good names. My favourite sectors to pick stocks from – Consumer Discretionary (XLY), Healthcare (XLV), Technology (XLK) and Communications (XLC). Technology stocks continue to deliver stellar earnings despite the rising yield curve concerns.

For specific stock recommendations, please do not hesitate to get in touch.

Best wishes,

Manish Singh, CFA