President Vladimir Putin’s actions make more hard-hitting economic sanctions against Russia inevitable. If Ukraine falls, will Putin move into Eastern Europe? What do past geopolitical events tell us about the impact on equity markets?

Summary

In 1945, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) argued that it needed “a buffer zone” around its borders, as it had been invaded by Germany in both world wars. It claimed that having a buffer zone would protect it against any future invasions. The Soviet Union went on to establish an extensive “buffer zone” by installing communist governments friendly to the USSR in the liberated Eastern European countries. So, here we are 77 years later and the “buffer zone” concept pops up again. This time, Ukraine is the “buffer zone” that Russia wants to preserve. This time, Russia feels threatened not by Germany, but by the expanded North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. We are stepping into a new period of uncertainly – a new Cold War. A new Cold War that has the potential to turn hot if Russian President Vladimir Putin feels more threatened and if China decides to join hands with him.

Putin’s actions make further and more hard-hitting US and European economic sanctions against Russia inevitable. It also raises the risk that, in a tit-for-tat, Moscow could play havoc with the energy market. Energy is the weapon that Putin can use against the West to deter them from coming to Ukraine’s help

So far, the debate for the March US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting has revolved largely around a +0.25% or a +0.50% interest rate hike. After this week’s events in Ukraine and with still three weeks to go till the meeting, if the situation in Ukraine worsens, I am not sure we’ll see a rise in US interest rates next month.

Sector-wise, so far in 2022, it’s essentially a sea of red for most equity sectors in the S&P 500 index. The stocks in the Energy sector (XLE), with average gains of +21%, has been living in an alternate reality however driven by inflation and the conflict in Ukraine. Stocks in the Financial sector (XLF) have managed an average YTD loss of -3% this year, and every other sector’s average YTD change is negative.

A lot of a bearishness is already priced in to equity markets and there is a likelihood that those expecting more bad news may be hit by three surprises – a de-escalation in Ukraine, the US Fed staying put on rates and inflation peaking as growth and consumption tumbles. There is room for a catch-up rally in equities. It’s time to build back equity exposure.

Russia’s desire for a “buffer zone” could start a new Cold War

In 1945, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) – the Soviet Union – came out of World War II with an aura of prestige from having beaten Hitler’s Germany at great personal cost. The total civilian and military deaths in the war in the Soviet Union is estimated to have been 24 million, which is nearly twice as many as in Germany, Poland, France, Italy and the UK put together.

Russia argued that it needed “a buffer zone” around its borders, as it had been invaded by Germany in both world wars. It claimed that having a buffer zone would protect it against any future invasions and in February 1945, US President Franklin Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin met at the Yalta resort, in then-Soviet Crimea, (see photo below) to finalize a post-war settlement.

At the conference the leaders agreed “to the right of all people to choose the form of government under which they will live. The three governments [US, UK, Soviet] will jointly assist the people in any European liberated state or former Axis state in Europe…to form interim governmental authorities broadly representative of all democratic elements in the population and pledged to the earliest possible establishment through free elections of Governments responsive to the will of the people.”

At the time, US Admiral William Leahy, Chief of Staff to Roosevelt said – “This [agreement on Poland] is so elastic that the Russians can stretch it all the way from Yalta to Washington without ever technically breaking it.” To which Roosevelt replied, “I know, Bill, but it is the best I can do for Poland at this time.”

Roosevelt died soon after in April 1945 and Vice President Harry S. Truman took over as the new US President.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, US President Franklin Roosevelt, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin at Yalta in February 1945

Source: US government holdings of the National Archives and Records Administration

Admiral Leahy’s concerns were proven correct, as Soviet armies took control of most of Poland and Eastern Europe and Stalin began installing Communist governments. It became clear by the Potsdam Conference in July 1945 that the Soviet Union had no intention of holding free and fair elections in the liberated Eastern European countries. By installing communist governments friendly to the USSR, the Soviet Union established an extensive “strategic depth” or “buffer zone” – the territory between a country and what it perceives to be hostile enemies – between the Soviet Union and the West.

Truman, the one-time farmer from Missouri, was rather naïve to start with and of Stalin, he observed – “I like him . . . he is straightforward.” French President Charles De Gaulle, by contrast, said Stalin was “a son of a bitch.” However, very quickly Truman became confrontational. The US had by then tested an atomic bomb and Truman knew he no longer needed Russian help in defeating Japan. The stage was set for the “Cold War” to begin, as the US and the USSR started distrusting each other. Truman’s policies came to be shrined in the “Truman Doctrine,” which positioned the US as the defender of a free world in the face of Soviet aggression. In the eyes of Stalin and successive Russian leaders the significance and need for a permanent and a wide enough “buffer zone,” were now set in stone.

So, here we are 77 years later and the “buffer zone” concept pops up again. This time, Ukraine is the buffer zone that Russia wants to preserve. This time, Russia feels threatened, not by Germany, but by the expanded North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. Therefore, the present conflict is part of the continuing fallout from the disintegration of the USSR in the early 1990s and Russia’s loss of the “buffer zone,” as NATO has expanded eastwards. Russia is a regional power in decline and feels insecure. It feels it is a victim of NATO’s eastern expansion and wants a restoration of its “buffer zone” and, with it, its lost influence. The United States, on the other hand, a global power unlike Russia, is also in decline as China rises relentlessly. The US, in the face of recent setbacks in Afghanistan and the Middle East and the growing military and economic threat of China, is similarly fearful of losing its sway in the world. As Asia gets prised away slowly from American influence, Europe is the region that the US wants to keep under its influence, for economic and strategic gains.

We are stepping into a new period of uncertainly, a new Cold War that has the potential to turn hot if Russian President Vladimir Putin feels more threatened and if China decides to join hands with him.

So, earlier this week, while announcing sanctions on Russia it was good to hear US President Joseph Biden point out – “Let me be clear: These are totally defensive moves on our part. We have no intention of fighting Russia. We want to send an unmistakable message, though, that the United States, together with our allies, will defend every inch of NATO territory and abide by the commitments we made to NATO.”

In the early hours of Thursday morning, Russia launched a military offensive on Ukraine. Putin, in an angry broadcast just before 6 am Moscow time called the operation a “special military operation” aimed to “de-Nazify” Ukraine. The Russian stock market, the MOEX Russia index plunged more than -30% in early trading and trading was halted.

Putin offered a chilling warning to any Western allies who might consider coming to Ukraine’s aide: “To anyone who would consider interfering from outside: If you do, you will face consequences greater than any you have faced in history. All the relevant decisions have been taken. I hope you hear me.”

Ukraine is not a member of NATO and therefore the US is not treaty-bound to enter into a war with Russia to defend Ukraine from falling into Russia’s hands.

Putin’s actions make further and more hard-hitting US and European economic sanctions against Russia inevitable. It also raises the risk that, in a tit-for-tat, Moscow could play more havoc with the energy market. Energy is the weapon that Putin can use against the West to deter them from coming to Ukraine’s help.

Russia has already been restricting the flow of natural gas it sends to the EU, with volumes down by more than a third compared with pre-pandemic levels. The risk now is that Putin further reduces the flow and cuts back on crude oil exports. Energy shortages in the EU, and a spike in US retail gasoline prices—now at a seven and a half year high of US$3.89 a gallon—will inflict political pain in Washington.

Putin will thus force the West to accept that Ukraine will not join the NATO and stay under Russia’s influence and be its “buffer zone” with NATO.

If Ukraine falls, will Putin move into Eastern Europe?

I believe it would be foolhardy and he would be risking his demise as the economic impact of his adventurism will snowball. Few would have predicted that it would be Germany that would offer the toughest response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. With a decisive move to shut down the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has thrust Germany into the vanguard of the West’s response to Russia. Germany is fearful of Russia on its doorsteps and it quite likes the “buffer zone” it has in Poland between itself and Russia. With Ukraine down, that buffer zone would wear thin and Germany would be wary of Russia’s move further eastwards.

No two conflicts are the same and we are in a vastly different world now with low interest rates and years of Quantitative Easing (QE) by central banks, however, it’s good to keep in mind how past geopolitical conflicts have affected equity markets. The chart below suggests that equity markets usually take conflicts in their strides – and move on.

The events that had the largest and the longest impact on the markets were – the Pearl Harbour attack and Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait – both involving the US military. The Munich Olympics attack in 1972 was also a big drag on the markets, but recall that the 1970s were also a period of continuous bad news – economic stagnation, high unemployment, an oil-shock, double-digit inflation, and the US dollar severing of links with the gold standard – weighing on overall sentiment.

How did the US equity market react during the last Ukraine-Russia conflict? In late 2013 and for the majority of 2014, Ukraine was central in the geopolitical news cycle, as Russia moved to annex Crimea. During this period, as shown in the table below, the S&P 500 index experienced increased volatility, but investors rushed to buy the dips.

Between November of 2013 and 2014, the S&P 500 gained +13.5%. During this period, the index traded down by at least -5% from a high on two occasions. So, from the perspective of US investors, there was little concern over Ukraine.

Source: Bespoke Invest

Now the question is, the present Russian incursion is closest to which event from all the ones listed above?

I‘d say – Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, given the Oil/commodity in focus, its impact on inflation and that an escalation of the conflict could drag US forces into the region via alliances. Having said that, the barrier to getting US forces involved in a conflict abroad with Russia is extremely high. Neither the US Congress nor the American people would support such a move given the chaotic manner (some would say ignominy) in which the US recently withdrew from Afghanistan.

As for the inflationary impact, the US is energy independent and has allies that can pump out more oil and gas. Besides, this being an election year, the Biden administration is acutely aware of “prices at the pump” and has repeated said it is going to “take robust action to make sure the pain of our [US] sanctions is targeted at the Russian economy not ours [US].”

In my opinion, interest rate increases and inflation are bigger concerns to the equity markets than the events on the Ukraine-Russia border.

Markets and the Economy

So far, the debate for the March Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting has revolved largely around a +0.25% or a +0.50% interest rate hike. After last night’s events in Ukraine and with still three weeks to go till the meeting, if the situation in Ukraine worsens, I am not sure we’ll see a rise in US interest rates.

The US economy rebounded from the Omicron wave in February, according to the latest flash Purchasing Manager Index (PMI) estimates by private data firm IHS Markit.

Both the manufacturing and service sectors recorded stronger expansions in output, with companies linking growth to substantial gains in new business, employees returning from sick leave, increased travelling and greater availability of raw materials. The composite PMI for the US rose to a two-month high of 56.0 in February from 51.1 in January. A reading above 50 indicates growth, while a level below 50 signals contraction.

European readings also showed accelerated growth driven by services providers. In the Eurozone, the PMI rose to 55.8 in February from 52.3 in January, the fastest rate of growth since September. In the U.K., the index jumped to 60.2 in February from 54.2 in January as output growth accelerated.

This week the S&P 500 (SPX) officially moved into correction territory – i.e., when a stock index falls by more than 10%. The tech-heavy NASDAQ index is down by more than -13% Year-To-Date (YTD).

Benchmark Global Equity Index Performance (2021 and 2022 YTD)

The February US inflation report, saw the inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) hit a 40-year high of +7.5%.

Despite this, the US yield curve continues to flatten, as the short-end 2y US Treasury yield rises faster than the long-end 10y US Treasury yield. If inflation were a major concern, for the medium to long term, one would expect long end yields to rise as well. The spread between the 2y yield and the 10y yield now stands at 0.38%. On the 10th of February (the day the inflation reading came out), this spread was at 0.55%.

This flattening of yield will not go unnoticed by the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and they will factor this into their rate decision due mid-March. This is happening at the time the Fed is still providing liquidity to the market. They’ve yet to make a final decision on monetary policy tightening.

I fail to see how the Fed could continue to raise rates, if the yield curve inverts i.e. 2y yield goes higher than 10y yield. I strongly believe that US inflation is close to peaking (more on this further down in the section) and will provide the Fed much-needed room to tone down hawkishness. As I wrote in last month’s Market Viewpoints, I do not see inflation as a concern. Disinflation in the medium to long term continues to be my base case for the US economy.

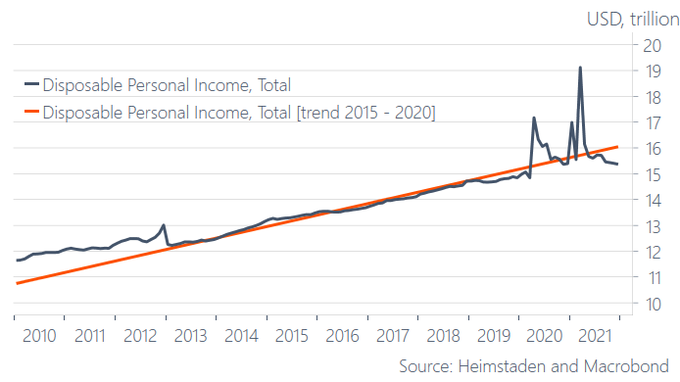

The chart below indicates that the US Disposable Personal Income (DPI) is no longer running above trend. As the growth in real disposable income declines, real personal consumption expenditure (PCE) – the Federal Reserve’s favourite measure of inflation – declines as well.

US personal disposable income (in trillion USD)

The elevated PCE that we have seen over the past three quarters is very likely a result of the pandemic shutdown, elevated growth in DPI led to savings uptick. With DPI now running below trend, the PCE will likely move back to a lower rate too i.e. we are at or near peak inflation in the US. And, if you are worried that a decline in DPI could be an indicator of a peak in GDP growth too, then let’s keep in mind that nothing ends inflation faster than an economic recession. A leg down in inflation is fast approaching.

The market sentiment as indicated by the AAII Net Bulls index ( The AAII Sentiment Survey is a weekly survey of its members, which asks if they are “Bullish,” “Bearish,” or “Neutral” on the stock market) is about as bad it has been in the last 20 years and is now the low levels we saw in May 2016.

Coincidentally (as the chart below indicates), it was also the time when the Fed had just embarked on a rate hike cycle with the first increase in rates. The sentiment bottomed after the first rate hike and improved thereon.

If the same were to happen this time, one would expect the equity markets to bottom in March-April, after the first rate hike and then to stay steady and climb upwards for the rest of the year.

The AAII weekly Bull-Bear sentiment survey, the US Fed fund rate and the S&P 500 index (2002-2022)

Source: Bloomberg

Sector-wise, on YTD basis, it’s essentially a sea of red for most equity sectors in the S&P 500 index. The stocks in the Energy sector (XLE), with average gains of +21%, has been living in an alternate reality however driven by inflation and the conflict in Ukraine. Stocks in the Financial sector (XLF) have managed an average YTD loss of -3% this year, and every other sector’s average YTD change is negative.

Sectors that have been the biggest laggards include Consumer Discretionary (XLY), Communications (XLC), Technology (XLK) and Real Estate (XLRE) with an average YTD decline of over -10%. Even in a traditionally defensive sector like Utilities, the stocks have already declined an average of -8.4% YTD.

Benchmark US equity sector performance (2021, 2022 YTD)

A lot of a bearishness is already priced in and there is a likelihood that those expecting more bad news may be hit by three surprises – a de-escalation in Ukraine, the Fed staying put on rates and inflation peaking as growth and consumption tumbles.

As I mentioned above, investor sentiment is currently very negative and there is room for a catch-up rally in equities soon. It’s time to build back equity exposure. In this period of elevated market volatility and geopolitical anxiety, structured products, which offer a degree of capital protection, continue to be a good way to invest, while at the same time helping pick good entry points in the market.

For specific stock recommendations and structured products ideas please do not hesitate to get in touch.

Best wishes,

Manish Singh, CFA